Choose How Your Furniture Business Will Compete – Low Cost, Differentiation or Focus.

Jack Young

- Last Updated: 6 November 2024

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways – Define Your Position

- Porter’s Generic Strategies: Michael Porter outlines three key competitive strategies: Cost Leadership, Differentiation, and Focus. Each strategy helps businesses define their unique position in the market.

- Importance of Positioning: Positioning is crucial for avoiding being “stuck in the middle.” A clear strategy ensures that all aspects of the business—operations, marketing, and product—are aligned and focused.

- Cost Leadership Strategy: Cost leadership enables businesses to offer lower prices by becoming the most efficient producer in the market, reducing costs through streamlined operations.

- Differentiation Strategy: Differentiation allows businesses to command premium pricing by offering unique value, whether through design, quality, or customer service.

- Focus Strategy: A focus strategy involves tailoring offerings to a specific niche or geographic market, meeting particular needs better than larger competitors.

- Porter vs. Mintzberg: Both Porter’s structured approach to strategy and Mintzberg’s emphasis on adaptability are valid. A successful strategy combines clear direction and adjusting flexibility based on real-world feedback.

What is Strategy?

Have you ever wondered why some companies thrive while others struggle despite having similar resources?

“Strategy 101 is about choices: You can’t be all things to all people.” — Michael E. Porter.

The Oxford Languages Dictionary defines strategy as “a plan of action designed to achieve a long-term or overall aim.” While this definition seems straightforward, it can be misleading.

“Strategy is not the consequence of planning, but the opposite: its starting point.” — Henry Mintzberg.

Strategy is not simply a plan of action. A strategy helps a business decide how it will compete, not just what it will sell. These deliberate choices define how the business will position itself in the market, what it will and won’t do and, ultimately, a way to sustain a competitive advantage.

A plan is how you execute the strategy, not the strategy itself.

Why is Strategy Important for Furniture Retailers?

It is incredibly difficult to stand out in the crowded furniture market. As discussed in our article on building loyalty in your furniture business, technology has significantly impacted the market by decreasing barriers to entry. Each month, new companies enter the market, most without a strategy. These businesses tend to adopt a “me-too” approach. If that shop sells that product, so will we.

This lack of clear distinction results in an overwhelming number of options for similar products, leading to challenges such as low footfall and fluctuating demand for business owners. Differentiating your business is essential for retaining and attracting new customers. This is where a well-defined strategy comes into play.

Without a clear approach, you risk blending into the market and becoming another option for consumers rather than a preferred choice.

In this article, we’ll discuss how you can use Porter’s

Generic strategies to choose your strategic position. This is the broad way in

which you are going to compete against your competition. It will need further

refinement—it is a positioning strategy, which is only part of the puzzle. We’ll

also discuss the importance of understanding the market realities that

influence these strategies. Successful businesses must remain flexible and

responsive to emerging opportunities and challenges, adapting their strategies

to truly thrive.

Michael Porter’s Generic Strategies

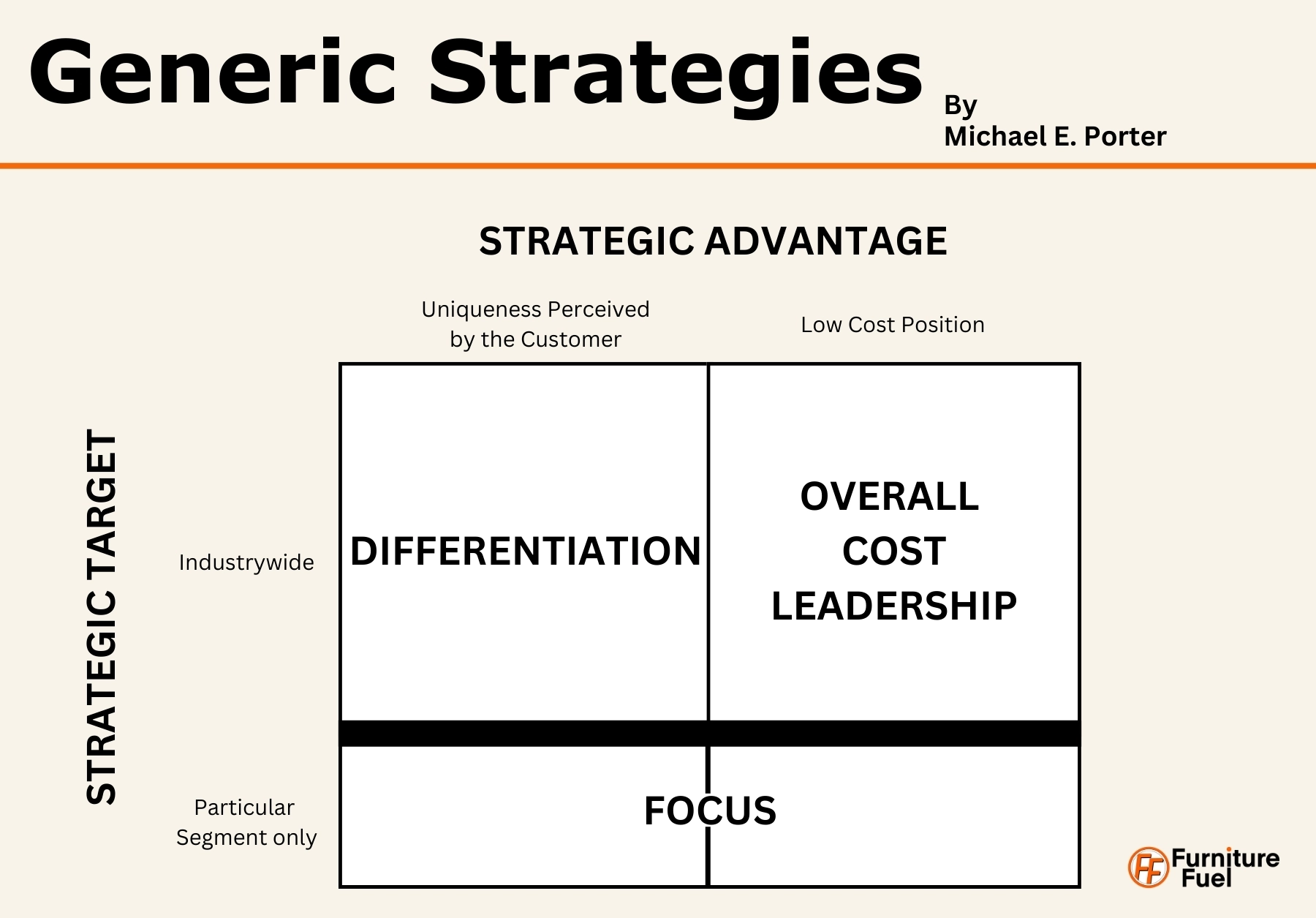

Michael Porter introduced the Generic Strategies framework in his 1980 book Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors.

In the book, Porter identifies three primary strategies that companies can use to achieve a competitive advantage:

- Cost Leadership: Becoming the lowest-cost producer in the industry.

- Differentiation: Offering unique products or services that customers value.

- Focus: Concentrating on a specific market segment or niche, which can also be divided into cost focus and differentiation focus.

Cost Leadership

“Cost Leadership requires aggressive construction of efficient-scale facilities, vigorous pursuit of cost reductions from experience, tight cost and overhead control, avoidance of marginal customer accounts, and cost minimization in areas like R&D, service, sales force, advertising, and so on. A great deal of managerial attention to cost control is necessary to achieve these aims. Low cost relative to competitor becomes the theme running through the entire strategy, though quality, service and other areas cannot be ignored.” – Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy, Overall Cost Leadership, Pg 35.

Cost leadership involves becoming the lowest-cost producer in the industry, allowing a business to offer lower prices than its competitors. This strategy can be particularly effective in budget-friendly furniture retail, where consumers are highly price-sensitive.

With this approach, retailers can reduce costs by streamlining operations, such as negotiating better deals with suppliers, standardising the product offering, and improving logistics and delivery processes, which can help cut expenses, allowing retailers to pass those savings directly on to customers.

Many business owners believe that price is their customers’ primary concern and, therefore, the main area they must compete on. While price is indeed a significant factor—especially during economic downturns—not all consumers are equally affected. For many, buying a product or service goes beyond price considerations.

Value is subjective. Customers may be willing to pay more for products that enhance their self-image or create perceived value beyond just the price tag. Understanding this reinforces the importance of knowing your target audience well.

People often use products and services to build their identity or social standing. A name-brand sofa, for example, might signal good taste, wealth, or an appreciation for quality. This kind of purchase provides social status or validation, making price a secondary factor compared to the overall value it creates for them.

It’s important to note that achieving a low-cost position is not a defendable strategy without ongoing investment. As Porter highlights, “Once achieved, the low-cost position provides high margins which can be reinvested in new equipment and modern facilities in order to maintain cost leadership. Such investment may well be a prerequisite to sustaining a low-cost position.”

In other words, reinvestment is essential to reinforcing and maintaining cost leadership. While this strategy requires investment—much like differentiation—the key is to ensure that every investment aligns with and strengthens the business’s position as a cost leader.

Differentiation

The Second generic strategy is one of differentiating the product or service offering of the firm, creating something that is perceived industrywide as being unique.” Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy, Differentiation, Pg 37.

Differentiation focuses on being unique in a way that customers value, whether through product quality, innovative design, or exceptional customer service. This strategy allows retailers to command higher prices due to their perceived added value.

“Differentiation provides insulation against competitive rivalry because of brand loyalty by customers and resulting lower sensitivity to price. It also increases margins, which avoids the need for the low cost position. The resulting customer loyalty and the need for a competitor to overcome uniqueness provide entry barriers.”

An example of differentiation in the furniture industry is Swoon. Known for its beautifully designed furniture, Swoon focuses on craftsmanship, in-house design, and premium materials. Swoon communicates these points where possible, including on its About Us page and its website’s benefit bar, where “Unique designs Crafted in limited-edition releases” is given priority.

A Screenshot of the benefit bar on Swoon’s Website

High-quality materials and stylish, timeless designs allow Swoon to attract customers looking for unique, high-end furniture that enhances their home decor, which often comes at a specific price point.

Focus

“The final generic strategy is focusing on a particular buyer group, segment of the product line, or geographical market: as with differentiation, the focus may take many forms.”- Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy, Focus, Pg 38.

The focus strategy involves concentrating on a niche market through cost leadership or differentiation. This approach allows retailers to tailor their offerings to meet the specific needs of a defined customer segment, resulting in stronger customer loyalty.

A focus strategy doesn’t just have to focus on a particular product or customer segment, though. A business can also achieve a focus strategy by “focusing” on targeting a specific geographical area.

Many local brick-and-mortar shops follow this strategy, even if unintentionally. For example, a furniture retailer in a town or city like Newcastle concentrates on serving the community by offering products that reflect local tastes and preferences.

By understanding the local audience’s needs and building relationships with this community, these retailers can create a loyal customer base that larger competitors might overlook.

Focus Low-Cost vs Focused Differentiation

“Even though the focus strategy does not achieve low cost or differentiation from the perspective of the market as a whole, it does achieve one or both of these positions vis-a-vis its narrow market target.”

While a focus strategy may not achieve overall market-wide cost leadership or differentiation, it allows businesses to excel in one or both of these areas within a specific market segment.

By narrowing the target audience, businesses can tailor their offerings more precisely, meeting the specific needs of that segment in a way that broader competitors cannot. This could mean creating unique, high-quality designs or offering a level of customer service tailored to a segment that large, more general competitors struggle to match.

Alternatively, a focus strategy might enable a business to become the low-cost leader within its niche by optimising operations and supply chains specifically for that segment. Since you aren’t required to appeal to the mass market, you can refine your processes and cut out unnecessary complexities or “fat” that broader competitors might need to retain to serve a larger audience.

Remember, when the term market or industry is mentioned, if you are following a focused strategy, then think of your geographical or niche offering as your market, not as the overall furniture market of the UK, for example.

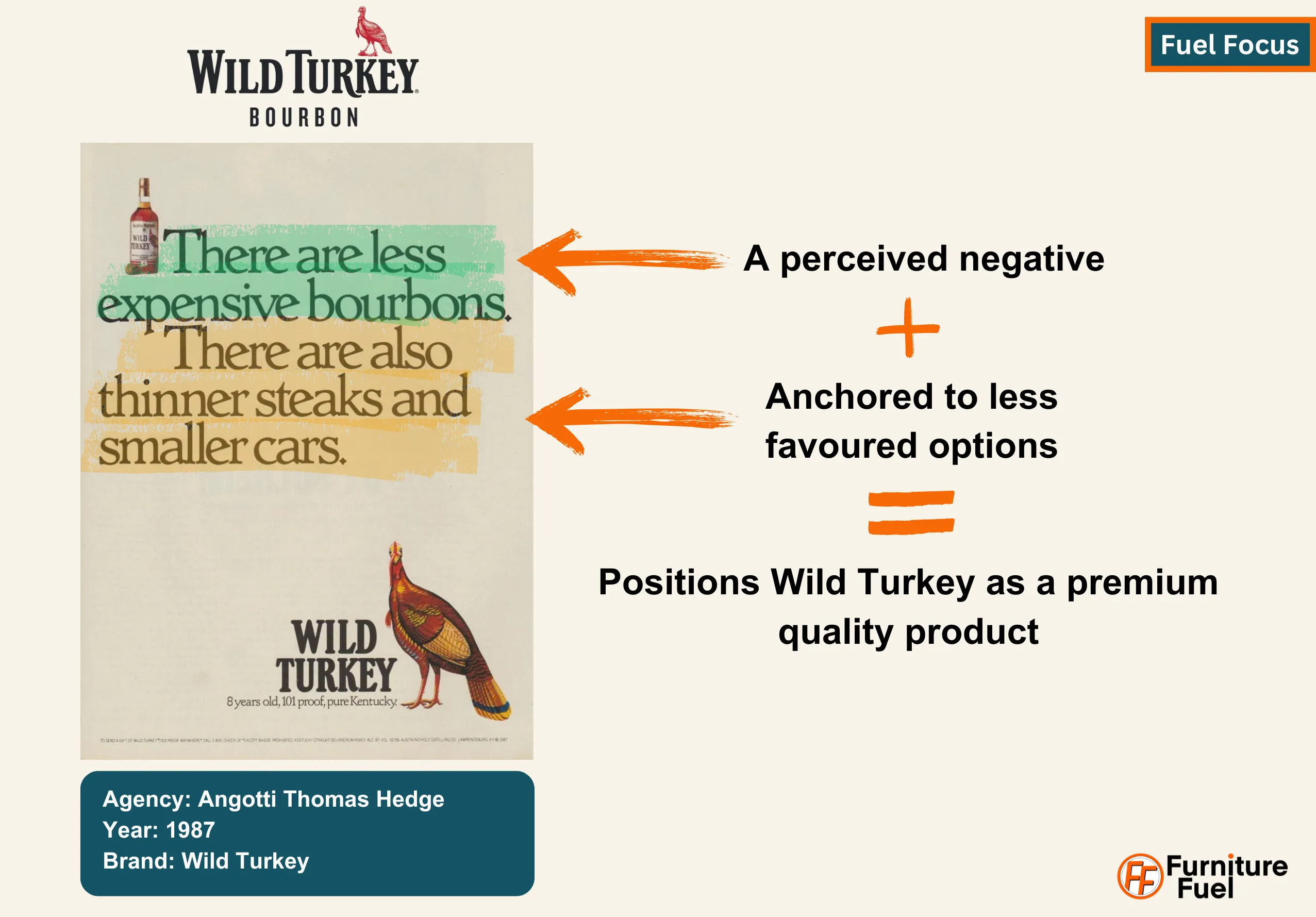

Fuel Focus - Wild Turkey AD 1987 - Differentiation

The 1987 Wild Turkey ad by Angotti Thomas Hedge positions the brand as a premium product, emphasising quality differentiation. The line “There are less expensive bourbons” acknowledges that more affordable options exist and combines transparency with reverse psychology.

They acknowledge a perceived negative of their product, which builds trust with the reader. However, they pivot quickly to position their product as superior, referencing “thinner steaks and smaller cars” to evoke emotional connections with less satisfying alternatives. They guide the audience to view Wild Turkey’s product as the “full experience,” implying that cheaper options are a step down in satisfaction.

They reinforce the value of their premium product through the psychological principle of the contrast effect, positioning it as superior without directly dismissing cheaper options—thereby avoiding alienation of potential budget-conscious buyers, who may buy Wild Turkey at a later date.

They have differentiated their product as better quality than the less expensive options, hence the price difference—lower price, lower quality.

You may also say this ad differentiates itself from others at the time. And yes, it does. Differentiation of advertising, though, should be a priority for all companies.

Standing out in a saturated market is essential. Simply blending in doesn’t attract attention. Generic ads fail to convey unique selling points, missing the opportunity to strengthen brand identity.

When an ad does more than just inform—like the bourbon ad by subtly associating itself with quality—it strengthens brand identity and attracts a specific type of customer.

The principles of differentiation are fundamental in the furniture industry, where many brands compete for consumer attention.

The Risks of Porter’s Generic Strategies

Porter also discusses the possible individual risks associated with the three generic strategies.

Recognising the risks is essential for ensuring that your chosen strategy remains effective in the long term. Below are the potential pitfalls of each strategy.

Cost Leadership Potential Risk: The Race to the Bottom

- Quality Erosion: In pursuing lower costs, businesses may make sacrifices that impact the quality of their products. If a company cuts too many corners, it risks alienating customers who expect a certain level of quality, even for budget items. Customers may perceive low cost as an indicator of poor quality, which can harm brand reputation in the long run.

- Overfocus on Efficiency: Businesses can become overly fixated on cost-cutting measures, leading to an internal culture where innovation, customer service, and long-term growth are deprioritised. This tunnel vision can limit opportunities for future expansion or adaptation to market shifts.

- Vulnerability to New Competitors: If a new entrant into the market discovers an even more efficient way to reduce costs, the original cost leader can find itself outcompeted. Technological advances, innovations in supply chain management, or geographic advantages might allow others to undercut your prices.

- Price Wars: Competing solely on price can result in aggressive price wars with competitors, eroding profit margins. While customers may benefit from lower prices, businesses involved in a price war may suffer from diminished returns, leading to unsustainable business practices over time.

Differentiation Potential Risk: The Balance Between Unique and Relevant

- Imitability: Differentiation only works if competitors cannot easily replicate the features or attributes that make your products unique. If your differentiation can be quickly copied, your competitive advantage will soon erode. For example, if you build your brand by offering unique furniture designs, competitors might follow suit with similar styles or even improve upon your innovations.

- Over-Differentiation: Businesses can sometimes differentiate to such an extreme that their products become irrelevant or unappealing to a large customer base. Products may become too niche, costly, or feature attributes that most of the market doesn’t value.

- Customer Perception of Value: Differentiation can fail if customers do not perceive the unique qualities of your products as valuable enough to justify the higher price. Without effective marketing that clearly communicates why your product is superior, customers may see no reason to pay more.

- Cost of Innovation: Staying ahead in a differentiation strategy requires continuous innovation. This can be expensive, requiring significant research, marketing, and product design investment. If a business cannot sustain this level of investment, it risks losing its differentiation advantage.

Focus Strategy Potential Risk: The Danger of Over-Specialisation

- Market Saturation: The business may reach a point where the targeted niche market becomes saturated, limiting further growth opportunities. In highly specialised markets, the number of potential customers may be capped, and once that ceiling is reached, expanding beyond the niche can be challenging.

- Vulnerability to Market Shifts: Focusing on a narrow segment makes a business highly vulnerable to changes in that segment. If customer preferences shift or new technology disrupts the niche, the business may struggle to pivot quickly enough to survive.

- Niche Competitors: Although a focus strategy aims to provide an advantage in a specific market, competitors may also target that niche. A rival could enter the segment with a more tailored product or superior service, diluting the original company’s advantage. If the market is small, it only takes a few competitors to impact your market share significantly.

- Lack of Diversification: Focusing too narrowly on one segment can expose a business if external forces change the environment. Without diversified revenue streams, a focused business may find it harder to absorb shocks like new regulations or unexpected disruptions like a pandemic. In contrast, more diversified competitors may be better equipped to handle these challenges.

As we will discuss further, incorporating flexibility into any strategy is vital for survival. As markets change or customer preferences shift, businesses must be agile enough to adjust their strategy while staying true to their core competitive advantage.

Industry Examples

Supplier low-cost leadership, Me-too Ranges

A supplier produces a popular range of furniture called “Trevi,” which has become a strong performer. Seeing its success, another supplier creates their own version of the Trevi range. Instead of differentiating their design, they copy the original (“me-too”), attempting to replicate the first supplier’s success. To undercut the original, this second supplier follows a low-cost leadership strategy by making subtle adjustments—thinner back panels, smaller tops and doors, cheaper, less durable materials for internal components and less time spent on finishing, leading to a noticeable inferior product.

The Problem

The second supplier uses the first Trevi range as an anchor—meaning they leverage the original product’s price and perceived quality to make their own version seem like a better deal. However, this “bad competition” approach lowers prices but also sacrifices quality. If the original supplier stops producing the Trevi range due to reduced demand, the second supplier can raise prices while still offering a subpar product. This undermines the overall market.

If consumers perceive furniture as overpriced, they tend to seek out the lowest-priced options, believing this to be a better deal. This shift in focus towards price can lead to a situation where manufacturing standards are lowered, and quality is further compromised. This creates a negative reinforcing cycle that ultimately harms the overall market.

Quality differences are often not immediately apparent to customers, who may resort to superficial checks like knocking on wood or lifting the product to assess weight—actions that don’t reveal true quality. This is where retailers play a critical role: educating customers on the differences in construction and materials. Trust between retailer and customer becomes vital, as the more informed the consumer, the more they appreciate the value of a higher-quality product.

A Note to Wholesale Suppliers

You play an important role in this process. Explain why your products are made the way they are—what makes them different. Help retailers sell your products. It’s a win-win.

Supplier Differentiation: The Paradox of Choice

While differentiation is often seen as a positive strategy, it requires careful planning to avoid unintended consequences. A great example is a supplier who pursued a differentiation strategy by offering each of their furniture ranges in three or more different colours. However, what seemed like a great way to provide options and cater to customer preferences, some of the colours were very similar, creating a problem.

This well-meaning approach created a paradox of choice. Instead of helping customers, the overwhelming number of options caused confusion and made it harder for them to make decisions. I saw this happen first-hand. Too many choices led to decision fatigue, and customers often walked away undecided.

This highlights why, even once you’ve decided on your positioning strategy, it still needs to be refined to ensure it achieves the desired effect. Simply picking a position doesn’t guarantee success—it requires fine-tuning to avoid pitfalls like the paradox of choice.

The paradox of choice refers to the phenomenon where an abundance of options can lead to anxiety and indecision rather than satisfaction. Although choice is generally perceived as a positive aspect of consumer behaviour, an overwhelming number of options can create confusion, making it difficult for customers to decide. This may result in feelings of regret and dissatisfaction, as consumers worry that they might have made a better choice had they selected a different product. Retailers must strike a balance by offering a range of options without overwhelming their customers.

We discuss common pitfalls like the ones above in our weekly newsletter. It’s straightforward, digestible content designed to fuel your furniture business.

There Can Only Be One True Low-Cost Leader

Porter argued that there can only be one true low-cost leader in a market because, by definition, the cost leader has the lowest operational costs and can offer lower prices while maintaining margins.

When multiple businesses compete aggressively on price, it often leads to a race to the bottom, eroding profit margins. If businesses continually undercut each other, the only real winner is the customer.

For many businesses, especially in niche or local markets, it makes more sense to acknowledge the dominant low-cost leader and differentiate instead.

This could involve focusing on other areas like customer service or product quality. In this case, combining a focus strategy (serving a specific area) and differentiation might allow a business to compete effectively without engaging in an unsustainable price war.

The Dangers of Being Stuck in the Middle

A common mistake mentioned by Porter is that businesses try to follow both low-cost leadership and differentiation at the same time, which can cause a situation called “stuck in the middle”. Companies attempting to compete on price while offering a differentiated product often lose ground on both fronts. They may not become the lowest-cost provider nor provide enough uniqueness to justify higher prices, leaving them vulnerable to competitors.

Pursuing differentiation typically incurs increased costs, as businesses generally need to invest in features that make them stand out in the eyes of consumers. On the other hand, low-cost leadership usually requires reducing operational costs to lower the prices of products or services. So, if a company tries to pursue both strategies at the same time, it may fail to achieve either.

While there are exceptions—such as needing to invest in technology to attain low-cost leadership—these cases are not the norm. Furthermore, differentiation supported by technology can sometimes be delivered at a relatively low cost. However, without a clear strategy, businesses risk becoming indistinguishable in a crowded market, ultimately compromising their profitability.

The Importance of Trade-offs in Strategy

“Strategy is about making choices, trade-offs; it’s about deliberately choosing to be different.” — Michael Porter.

Businesses must choose which activities to pursue and which to avoid, and these choices define what they will excel at. Companies can’t be everything to everyone without risking being “stuck in the middle.”

IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad was determined to offer the best possible prices but not at the expense of quality. He recognised that while some competitors might “cheat” on quality to lower costs, he was unwilling to make that trade-off.

The Criticism: Mintzberg vs. Porter on Hybrid Strategies

“Strategies grow initially like weeds in a garden; they are not cultivated like tomatoes in a hothouse”— Henry Mintzberg.

Porter’s caution about pursuing cost leadership and differentiation as a deliberate strategy is valid. However, no discussion of Generic Strategies would be complete without addressing Henry Mintzberg’s critique of this approach.

Henry Mintzberg, another noted author and strategist, criticised rigid approaches, arguing that, in practice, businesses often successfully blend these strategies.

“Thus, we concluded that strategies are to organizations what blinders are to horses: they keep them going in a straight line but hardly encourage peripheral vision.”— Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and Lampel – Strategy Safari.

Mintzberg was not adamantly against any particular school of thought in strategy. He believes that certain ways of planning strategy, even if implemented successfully, could put blinkers on the business. They don’t see emergent strategies, which emerge organically over time as businesses respond to market forces, customer feedback, and unforeseen challenges.

Differentiation could emerge as a byproduct of a firm’s actions, not a deliberate choice, but in my opinion, this doesn’t directly oppose Porter’s framework.

Porter did say that a cost leadership strategy could naturally reveal areas of differentiation. For example, a company that optimises its supply chain to lower costs might offer faster delivery or better efficiency, which customers could perceive as a differentiator. But warns that if you deliberately focus on both without a clear strategy, you risk diluting your efforts and losing competitive advantage.

For example, a local furniture store might start with a focused low-cost approach, only to discover that its customers are more interested in higher-end, customisable furniture. Rather than rigidly sticking to its original strategy, the business evolves its approach incrementally—an approach Mintzberg would argue is more reflective of real-world strategy.

The IKEA Example: Combining Cost Leadership and Differentiation

IKEA is an example of how pursuing one strategy can naturally lead to elements of the other, creating a hybrid strategy.

Initially, IKEA wanted to reduce the high cost and damage caused by delivering furniture by mail. Their solution? Flat-pack furniture. This not only solved the damage problem but also became a point of differentiation. And although not known then, customers being able to assemble their furniture at home can reinforce the value of the product through what is called, funnily enough, the IKEA effect.

The IKEA effect highlights how consumers often place a higher value on products they have invested effort into assembling or personalising. This phenomenon suggests that when individuals participate in the creation or assembly of a product, they develop a stronger emotional attachment to it, leading to increased satisfaction and perceived value.

Additionally, IKEA strategically chooses out-of-town locations for its stores, lowering its initial investment and ongoing cost while offering more parking spaces and inventory space for same-day collection than high-street locations—a further differentiator from competitors.

IKEA’s approach demonstrates how a business can achieve low-cost leadership and differentiation.

IKEA’s Strategic Consistency

Porter would argue that IKEA’s success comes from its ability to maintain strategic consistency. Every decision—flat-pack furniture, store locations, product design— is aligned, creating a hard-to-imitate system that reinforces its unique position in the market. This “fit” between its activities makes IKEA’s strategy harder to copy, giving it a sustainable competitive advantage.

Dynamic Capabilities

IKEA also benefits from Dynamic capabilities, first introduced in David J. Teece, Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen’s paper Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management, 1997.

Dynamic capabilities are essential for businesses operating in today’s rapidly changing market environments. They refer to a company’s ability to quickly adapt and reconfigure its resources and strategies in response to changes in the market and technology. Essentially, it’s about responding effectively to new challenges and opportunities as they arise.

This concept aligns well with Mintzberg’s incrementalism and emergent strategies. Both ideas focus on a business’s ability to adapt and respond to market changes rather than strictly following a pre-defined, deliberate strategy.

Operational Effectiveness Is Not Strategy

Operational Efficiency: The ability of a company to deliver products or services at the lowest possible cost while maintaining high quality.

Many businesses assume that being more efficient—doing things faster, better, or with fewer resources—is enough to outperform competitors. While operational efficiency can provide a competitive edge, it’s not the same as having a comprehensive strategy. Efficiency gains may improve performance in the short term, but without a clear strategic direction, they often fail to deliver a lasting competitive advantage.

In his Harvard Business Review article, “What is Strategy?” Porter argues that, though necessary, operational efficiency is not a substitute for strategy. True strategy involves making unique choices that distinguish your business in the market. It’s not just about working more efficiently —it’s about deciding where to focus your efforts and what not to do, ensuring that your competitive advantage is sustainable over time.

Operational efficiency can be a key component of any strategy, whether you are pursuing cost leadership or differentiation. For companies focusing on differentiation, operational efficiency is vital for supporting higher-quality products or more innovative services without letting costs spiral out of control. Even businesses that offer unique products or services must ensure their operations are streamlined to maintain profitability and reinvest in innovation.

IKEA’s low-cost leadership isn’t just about cutting corners but maintaining strategic alignment across all areas of the business. Their operational efficiency—through flat-pack furniture, out-of-town store locations, and streamlined supply chains—supports their larger strategy, allowing them to offer low prices while still standing out in the market.

Applying Generic Strategies to Your Business

Every business must choose a clear strategic path to stand out. Now that we’ve explored Porter’s generic strategies, it’s time to think about how they apply to your own business. Consider the following questions:

- Are you trying to compete primarily on price? Are you the low-cost leader in your market?

- Do you offer something unique that customers are willing to pay more for, like premium quality, design, or service?

- Are you focused on serving a niche market, catering to a specific customer segment or region? If so, are we focused on low cost or focused on differentiation?

Which of the three strategies—cost leadership, differentiation, or focus—best aligns with your current business approach?

If unsure, consider what sets you apart from your competitors or how you aim to win customers. You can always ask your customers what they think. Remember that there is generally only one genuine low-cost provider in a market. And whilst you may not compete on price and follow a differentiation strategy, ensure you’re not falling into a “me-too” differentiation strategy, where you believe you offer a unique proposition, but in practice, it mirrors what competitors provide.

Life isn’t static, and neither is Strategy. Collect data and feedback regarding the direction you have chosen. Other strategic areas may emerge, which you should investigate for competitive advantage.

As we continue exploring strategy, we’ll examine how external forces shape your approach and what it takes to adapt to a fast-changing market. But now is the perfect time to revisit your business model, evaluate how you fit into Porter’s strategies, and ask if that is the right direction for your business.