What U.S. Furniture Tariffs Really Mean for UK Retailers

Jack Young

- Last Updated: 16 November 2025

TL;DR - Will the U.S. Tariffs Affect Your Furniture Business?

While aimed at boosting domestic manufacturing and jobs in the U.S., these tariffs disrupt established global trade grounded in comparative advantage, leading to potential container imbalances, higher shipping costs, and supply chain volatility worldwide.

Historical examples, such as the Chicken Tax and recent solar panel tariffs, illustrate how politically motivated trade measures often become long-lasting fixtures that are difficult to reverse, especially once domestic jobs are created. Chinese government subsidies further complicate the landscape by enabling factories to absorb some tariff costs, making price reductions for UK retailers unlikely.

UK furniture retailers should not expect lower prices from these tariffs; rather, they face the prospect of more costs and disrupted supply chains. Strategies such as diversifying suppliers beyond a single country, adjusting stock management to add a buffer against delays and price movements, and maintaining close relationships with freight forwarders are and remain essential.

The tariffs cause major shifts, not short-term disruptions, that challenge traditional trade efficiencies and stress the importance of quality, service, and brand trust for retailers to succeed in a volatile market.

Note on Import Values:

Figures for U.S. furniture imports can vary slightly between sources. This is often due to differences in how trade categories are defined, such as HS codes, which subcategories are included, reporting periods, and valuation methods. All figures are intended to illustrate general trends rather than precise totals.

Table of Contents

The U.S. Furniture Tariffs

President Donald Trump announced on his Truth Social platform that a big, beautiful major investigation into tariffs on furniture imports to the United States was underway. His “Truth”, which is the platform’s equivalent of a “tweet”, stated:

“I am pleased to announce that we are doing a major Tariff Investigation on Furniture coming into the United States. Within the next 50 days, that Investigation will be completed, and Furniture coming from other Countries into the United States will be Tariffed at a Rate yet to be determined. This will bring the Furniture Business back to North Carolina, South Carolina, Michigan, and States all across the Union. Thank you for your attention to this matter!”

The market responded quickly. Publicly traded U.S. furniture retailers, such as Wayfair and Williams-Sonoma, experienced declines in their stock price, while the U.S.-based manufacturer La-Z-Boy saw its share price rise. Williams-Sonoma was affected during Trump’s first term and the U.S.-China trade war. To reduce tariff risks, they shifted some manufacturing out of China, instead moving production to Indonesia, Vietnam, and setting up domestic manufacturing in Mississippi.

In May 2019, Williams-Sonoma’s CEO told CNBC that the company had moved some furniture production out of China to countries including Indonesia, Vietnam and the United States in anticipation of additional tariffs. In December 2018, the company announced it would open a manufacturing facility that would produce upholstered furniture in Tupelo, Mississippi—a move that would create hundreds of jobs in the United States. (Trade War, Containers Don’t Lie, Lori Ann LaRocco, p.147).

Although William-Sonoma opened its Sutter Street Manufacturing subsidiary in Baldwyn, Mississippi, producing upholstery for brands like Pottery Barn (soon expanding to the UK), it was not immune to the initial market shock triggered by Trump’s announcement.

The question remains: why didn’t the company move all its production to the U.S. if tariffs posed a risk? The answer lies in Asian manufacturing’s comparative advantage.

Comparative Advantage and Global Trade

Global trade is driven by specialisation. Countries focus on producing certain goods or services rather than trying to do everything themselves.

In theory, this specialisation is guided by comparative advantage, the idea that countries benefit by producing what they can make at the lowest opportunity cost, even if they aren’t the absolute most efficient at it. Absolute advantage, being more efficient overall, also matters, but comparative advantage explains why trade can be mutually beneficial.

For instance, Vietnam is better positioned to manufacture furniture due to its skilled workforce and lower cost for production, while the UK has a comparative advantage in high-value sectors such as design, marketing, and retail. By focusing on what each can produce most efficiently, both countries can trade to mutual benefit, resulting in lower prices and more choices for consumers.

However, global trade is rarely a simple exchange between two countries. The reality is a complex, multi-layered system influenced by international supply chains, political decisions, and advances in technology.

The complexity of the system is precisely why the tariffs are disruptive.

What is Opportunity Cost?

Opportunity cost is simply what you give up when you choose one option over another. For retailers, this often comes down to where you put your resources—money, time, store space, or people.

Example 1: Sourcing & Strategy

- Option A: Manufacture your own furniture.

Gain: Greater control over production, potentially higher quality.

Give up (Opportunity Cost): The chance to invest those resources in brand, marketing, and customer experience.You trade time and money resources to pursue manufacturing, which raises costs, but could deliver a better-made product. You may also lose the chance to build manufacturing as a long-term competitive advantage.

- Option B: Source from a specialist factory in Vietnam.

Gain: Lower costs and the freedom to focus on what makes you different.

Give up (Opportunity Cost): Ownership and control of your manufacturing process.By outsourcing, you free up resources to invest in retailing, marketing, and building overall brand equity. In doing so, you focus your efforts where they create the most value—your brand, your store experience, and your customer relationships. However, you also give up direct control and may risk your supplier working with competitors.

Example 2: Everyday Retail Trade-off

- If you dedicate prime store space to low-margin products, the opportunity cost is the profits you could have made by featuring bestsellers instead.

- If you move your store out of town to cut costs, the opportunity cost is the higher passing foot traffic you traded away.

Every decision has a trade-off, the cost of the next best alternative you didn’t choose. Opportunity cost isn’t about “losing.” It’s about choosing the option that delivers the highest return for your business.

Why Tariffs Disrupt Comparative Advantage

Tariffs disrupt the “mutually beneficial” system established by comparative advantage. When a country imposes tariffs, it artificially increases the cost of imported goods, undermining the natural global efficiency gained through free trade. The US, by introducing tariffs, is effectively stating: “We prefer domestic production, regardless of overseas cost advantages”, or sometimes, perpetuating the misconception that trade partners pay the US to sell goods there.

The Soybean Saga Example

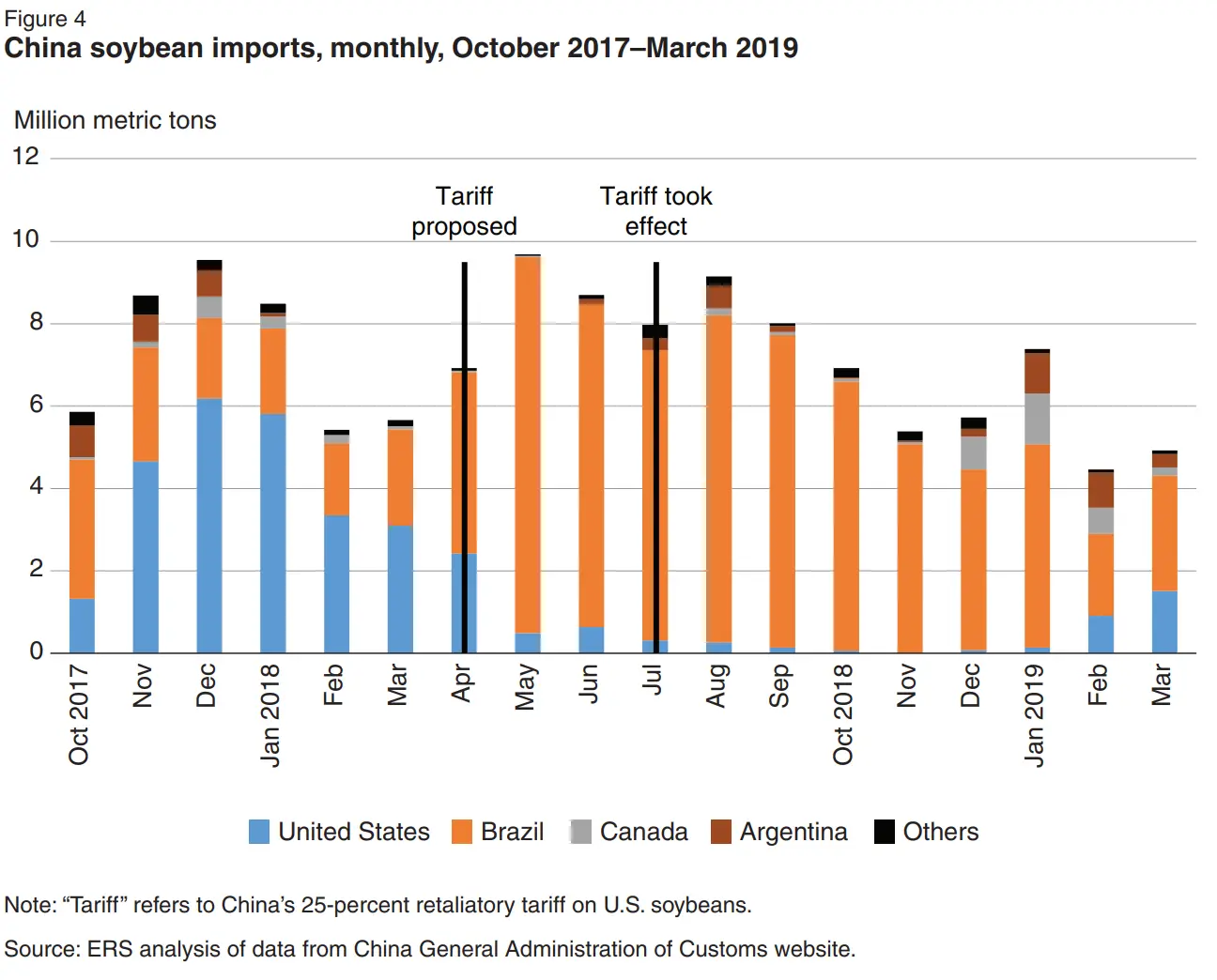

One clear illustration is the soybean trade war. When China retaliated against US tariffs by imposing its own on US soybeans, Chinese buyers quickly looked for alternative suppliers. Brazil, with its comparative advantage in soybean farming, filled the gap. This example shows that tariffs do not stop international trade but redirect it, often creating a less efficient and more volatile system.

As a result, US soybean export prices dropped significantly due to the loss of a major buyer. Meanwhile, Brazilian soybean prices surged as China’s demand shifted. These soybean price movements have reappeared in recent tariff conflicts, as global demand adjusts and costs fluctuate.

US soybean exports to China fell by over 75% (2018), causing billions in losses for American farmers. Although soybean prices eventually recovered, they only returned to pre-tariff levels and did not exceed them, illustrating that tariffs often harm the very domestic interests they aim to protect by triggering unintended economic consequences.

It’s important to note that an outbreak of African swine fever in China further reduced soybean demand, compounding the market disruption. Even though the UK is not a major soybean importer, disruptions on major trade lanes have a ripple effect and introduce instability throughout supply chains worldwide.

Source: Interdependence of China, United States, and Brazil in Soybean Trade, OCS-19F-01, by Fred Gale, Constanza Valdes and Mark Ash, 6/28/2019

In an age of AI, Truth Social Presidents, and constant change, make sure you stay informed—subscribe now.

Tariffs' Effect on Factory Pricing and Supply Chains

When discussing tariffs on U.S.-imported furniture, China is often the first country that comes to mind.

Although Vietnam has surpassed China as the top furniture exporter to the US, this article uses China as a primary example to understand global trade retaliation, policy responses, and market disruption. China’s previous reactions to tariffs are better documented, providing valuable lessons on how supply chains and pricing may be affected.

Vietnam, while officially a communist country, operates a socialist-oriented market economy that is relatively hands-off, allowing private enterprise and market forces to drive rapid export growth.

Much of Vietnam’s furniture manufacturing success is linked to China through investment, technology transfer, and integrated supply chains. Chinese furniture manufacturers established facilities in Vietnam to follow their foreign clients’ ‘China Plus One’ diversification strategies—helping those clients reduce tariff exposure while still leveraging Chinese expertise.

The “China Plus 1” strategy refers to a supply chain and sourcing model where companies diversify manufacturing by adding at least one other country alongside China. This approach has gained importance due to geopolitical tensions, tariff risks, rising labour costs in China, and the need for more resilient supply chains, especially after disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic. Vietnam has emerged as a leading “plus 1” destination, offering competitive labour costs, favourable trade conditions, and geographic proximity to China.

Rather than replacing China, Vietnam expands the network. China continues to dominate in high-tech inputs, advanced components, and unmatched scale, while Vietnam provides flexibility, resilience, and access to favourable trade agreements. Together, they form an integrated ecosystem rather than a zero-sum choice.

Source: APLF, Vietnam and ASEAN Furniture Industry Material Demand Surges with U.S. Import Growth, 12 June 2025

Vietnam’s previous pricing advantage has eroded due to recent tariff implementations. Predictions have been made that export volumes could slow, putting Vietnam’s position as the top US furniture exporter at risk.

“Exports to the U.S. have surged, leading to high inventories. We have to recognise that in the last half of 2025 and the first half of 2026, shipments of wooden furniture, textiles, and similar goods to the U.S. will likely slow,” Phu said.- Vu Ba Phu, director of Vietnam’s Trade Promotion Agency.

Finally, China remains the largest furniture importer by country to the UK. So, it can be reasonably assumed that how tariffs affect China will have the greatest impact on the UK furniture market.

US Furniture Tariffs' Effect on China

“In 2024, China exported $36.6B of Other Furniture, being the 15th most exported product (out of 1,211) in China. In 2024, the main destinations of China’s Other Furniture exports were: United States ($9.34B), Australia ($1.73B), Malaysia ($1.64B), United Kingdom ($1.6B), and Japan ($1.51B). The fastest growing markets for Other Furniture exports in China between 2023 and 2024 were: United States ($365M)” — OEC

Note: The category “Other furniture” is usually associated with Harmonised System (HS) code 9403, which covers furniture and parts thereof that are not elsewhere specified. This includes most household and office furniture except seats (which are covered by HS 9401), medical/surgical furniture (HS 9402), and bedding/mattresses (HS 9404).

China historically takes threats to its economic interests seriously. This was evident during the recent trade wars with the US, which saw a tit-for-tat escalation of tariffs and retaliations, with maximum tariffs reaching as high as 145%.

So, how might China respond if the latest US furniture tariffs are implemented?

Chinese Factory Prices

Let’s be clear, the importer pays the tariff, not the manufacturer or exporting country. A US-based furniture retailer importing a container of sofas is the one who pays the tariff at the US port. The Chinese factory, or any other country of export factory, in theory, is still getting paid the same amount for the goods themselves.

Whilst an importer can negotiate a price reduction with the factory to offset tariff costs, the manufacturer is not required to do so. If the importer really needs that specific product and can’t find it elsewhere, the more the importer will have to bear the cost. However, if the shelf price of the product becomes more than the customer is willing to pay, then a sharp drop in demand is a problem for the factory.

Simply, fewer products produced reduces cost allocation efficiency. Manufacturing typically relies on economies of scale—the more units produced, the lower the cost per unit. Economies of scope also apply. For example, using the same materials (like oak) across product lines enables bulk purchasing, further lowering costs.

When US orders decline or disappear, factories face excess capacity, idle workers, and fixed costs such as rent, utilities, and machinery that must still be covered.

In such cases, factories are unlikely to drop prices in the U.S. or for everyone else, for that matter, to stimulate orders. Short-term discounts may occur to clear excess stock, but this approach is not sustainable long-term. Additionally, price drops may feel beneficial temporarily, but indicate an unhealthy market system—a symptom of a sickness.

In the short term, if tariffs are imposed, it will be business as usual to see how demand reacts to price changes.

Often, price increases are blamed for demand drops, but public perception and media attention play a significant role. Consumers may rally to buy American-made products out of patriotism, causing imports to slump, with tariffs cited as the bad actor.

The Long-Term Response to Tariffs

Increased cost will eventually be passed on to the consumer, but what it demand decreases?

A common response to impacted margins and high costs is to reduce production costs. This would be the most likely course of action to relieve the tariffs’ impact. Although much here is speculative until the tariff details are known, cost-cutting measures are common.

For example, products arriving with thinner back panels, doors, tops, and bases, reduced timber thickness, often referred to as Skimpflation and a reduction in the overall size of the product, Shrinkflation, have been seen in the industry.

In the tariff context, it’s a strategic reduction in size and quality to make the product more viable in the market rather than the conventional use of either. While this may seem a practical short-term solution, it erodes market perception over time.

Customers often say “things are not made like they used to be” because price has remained stable while quality and size have decreased. Thus, prices no longer reflect product value, leading consumers to seek cheaper alternatives. Often, when customers say products are too expensive, they mean the price doesn’t match the quality, not that the price itself is inherently high.

Customers are professional consumers—they notice changes in products.

Past trade wars have shown that Chinese companies’ long-term response includes diversifying away from the United States. They seek new markets in Europe, Southeast Asia, and domestically to reduce reliance on a politically volatile major customer.

The irony is that while Chinese companies are diversifying away from the U.S. to reduce risk, other countries are simultaneously diversifying away from China for the same reason—everyone is trying to avoid putting all their eggs in one basket.

Price Drop and Market Erosion

Earlier, it was said that “price drops may feel beneficial temporarily, but indicate an unhealthy market system”, but what does that mean?

Price drops, when they are systemic rather than strategic, usually indicate several concerning market conditions:

- Oversupply relative to demand: Factories cut prices not because they are more efficient, but because they cannot sell what they have produced. This signals a market out of balance.

- Eroding margins: When discounts become the primary way to move stock, profitability across the supply chain, from factories to importers to retailers, collapses. Without profits, businesses struggle to reinvest, innovate, or maintain quality.

- Race to the bottom: Competing solely on price drives quality down and conditions customers to expect continual discounts, weakening the long-term health of the industry.

Disproportionate Impact on Smaller Retailers

Discounted stock from factories often flows to larger buyers who can order in bulk, pay upfront, and move product quickly. Smaller retailers rarely get access to these lower prices, yet they still face the pressure to match the discounted rates in the market. The result is that margin erosion hits smaller businesses hardest. They cannot compete on scale or cost, and their profitability suffers disproportionately.

In a scenario where tariffs on furniture cause prices to drop for everyone else, the only real winner in the short term is the consumer. However, increased shipping costs and supply chain disruptions (discussed later) could offset or even eliminate those temporary savings.

For businesses, the longer-term effect could be market erosion caused by an influx of cheaper products.

- Price perception: When prices temporarily drop, customers get used to them. When the market inevitably corrects and prices rise again, customers may feel unfairly treated or “ripped off.”

- Supplier instability: A supplier who is forced to sell at a loss to stay afloat is not a stable long-term partner. They may cut corners on quality, and they are at high risk of going out of business.

- Brand devaluation: For mid-to-high-end retailers selling quality furniture, a flood of cheaper alternatives makes it harder to justify premium prices.

As a furniture retailer, your role is not just selling products but building a sustainable business with a consistent brand image and customer experience. Market volatility, whether up or down, is a threat to that stability.

Is a reduction in wholesale prices as impossible as this article suggests? Is there a way for an American tariff to be imposed and yet keep the product’s price and quality unchanged?

Now, we come to the elephant in the room—government subsidies.

Chinese Government Trade Subsidies

Let’s consider, for argument’s sake, a scenario where a flat 20% tariff is applied globally in place of all other tariffs.

Yes, I know—unlikely. Governments value tariffs as strategic tools, rewarding partners, protecting industries, and “shaping” negotiations, making such a simplified system more of a thought experiment than a likely reality. More likely, tariffs will be applied on a country-by-country basis, on top of other tariffs, which will make little sense to the global market.

Price Reductions Without a Loss

The most logical point in the supply chain, from manufacturing to consumer, for cost reduction while maintaining product quality is, in this case, the manufacturing factory.

Chinese furniture manufacturers’ profit margins are already squeezed to stay competitive. A price drop of the kind required to absorb a 20% tariff would likely mean selling at a loss, which no business can sustain indefinitely.

However, their ability to absorb such tariffs may not come solely from their own thin profit margins but from government intervention.

A 2024 IMF report titled “Trade Implications of China’s Subsidies” showed that China supports its furniture manufacturing industry, positively affecting sales and exports. (Source: IMF report)

On page 18, under Table 1: Effects of China’s subsidies on trade in targeted products, it states:

“For instance, in the electrical machinery and furniture industries, subsidies are found to foster exports while reducing imports.”

Furniture is mentioned again on page 28 under Table 3: Effects of China’s subsidies on export prices and quantities:

“The findings indicate that China’s direct subsidies have pushed towards greater supply and lower prices in the communication equipment, plastic, chemicals, metal products, wood and furniture industries.”

In concluding remarks on page 31, the report states:

“Across industries, the impact of subsidies on exports is strongest for electrical machinery and furniture, while for metal products subsidies significantly lower both exports and imports.”

From this IMF report, it is clear that the Chinese government supports the country’s furniture manufacturing industry with subsidies that have a positive impact on export volumes.

Historically, Chinese government subsidies take many forms, including direct monetary transfers, tax breaks, export tax rebates, and preferential loans. The objective isn’t solely to be profitable but to maintain production volume and market dominance, even in the face of tariffs or falling demand.

Manufacturers can reduce the price at the factory because the government is effectively covering a portion of the cost, allowing them to maintain market share by selling products below the true cost of production.

When a tariff is imposed, it’s a test of wills. The US government aims to make imports more expensive, while the Chinese government may counter with subsidies or tariffs of its own. This is effectively a trade war funded by taxpayers or a push to force the US to reconsider by making US exports to China more costly.

Any factory price reductions through government subsidies are unlikely to be officially announced. Admitting such strategies would reveal ways around tariffs and likely provoke increased tariff measures.

China Subsidies and Comparative Advantage

A quick note on China in relation to comparative advantage mentioned earlier. These subsidies interfere directly with what should be a natural market system. They are considered anti-competitive behaviour. China’s comparative advantage in manufacturing owes much to its industrialisation efforts, which the West exploited for cheap labour and government subsidies. However, China now genuinely holds a comparative advantage in many markets due to significant innovation, which is seen in electric vehicles (EVs) and battery technology.

The Reality of Chinese Subsidies on Furniture Prices

If a Chinese factory uses subsidies to sell to a US importer at a price 20% lower to offset tariffs (assuming that is the tariff rate), what does this mean for UK retailers?

It means the US importer might still be buying furniture at a price very close to what they were paying before. This undermines any hope of a significant price reduction for UK buyers.

UK retailers are unlikely to see a price drop because China’s subsidies and global reach primarily offset the impact of US tariffs. However, Vietnam’s market is different. If US imports slump, Vietnamese suppliers could be forced to adjust export strategies, potentially influencing prices or availability for UK buyers as well.

China has been the main focus so far, but these tariffs don’t just threaten China. Broad protectionist policies, particularly on this scale, risk disrupting global trade rather than freeing up resources elsewhere.

The biggest threat—disruptions to container shipping.

The Container Pricing Paradox

At first glance, fewer products being imported to the U.S. might suggest that more containers would be available for other countries, leading to less demand and lower shipping prices.

The paradox is that the opposite can often be closer to reality.

The Global Imbalance of Containers

Less trade going to the U.S. doesn’t necessarily free up containers for the rest of the world. Instead, it can create a significant surplus of containers stuck in U.S. ports and a shortage in Asia.

The container shipping industry operates on a finely tuned, but fragile, balance. Most of the global trade is directional. Full containers flow from major manufacturing hubs like Asia to consumer markets such as the U.S. and Europe.

Containers are most valuable when they are full of goods, as shipping companies earn revenue on outbound journeys from Asia. The challenge is getting those empty containers back to Asia efficiently and affordably to be refilled for the next trip.

A tariff wrecking ball Incoming!

During the U.S.–China tariff wars of 2018–2019, Importers rushed to beat impending tariffs by ordering larger quantities in advance, a process known as front-loading.

Front-loading, when done on a large scale, creates shortages of containers. More containers are needed to transport the increased stock. This, and the reduced available container space and can drive shipping prices up.

An increase in manufacturing demand can also mean that when operational capacity (the amount you can produce) is near max, something normally gives, such as quality or machinery, which results in increased cost, time and most importantly, brand damage.

Ports have finite storage capacity, which, during the first Trump-era trade war, quickly became overwhelmed. Containers sat on truck chassis used as makeshift storage, reducing chassis availability for container transport. Creating an artificial driver shortage and increasing the price of transport.

“The impact of this unintended trade war consequence was simple: Longer waiting periods for both chassis and cargo ate into the movement of the containers. “Instead of a driver moving three containers, they may only be able to move one,” said LaBar. “This created an artificial trucker shortage. There were enough drivers to move the cargo. It was the system that was hindering the process.” (Trade War, Containers Don’t Lie, Lori Ann LaRocco, p.125).

Earlier, it was suggested that a global tariff might be preferable because tariffs increase paperwork and inspection requirements. A non-global tariff requires customs to verify the country of origin and classification codes to determine rates, slowing goods flow and causing terminal backlogs. While a flat global tariff doesn’t eliminate these issues, it simplifies them.

Demand Slumps After the Surge

Consumers also front-load their purchases.

The UK saw a situation of front-loading where the VAT was moved back to 17.5% from 15% (2008-2010). People were moving up their time scale of purchase to beat the increase.

When consumers advance their purchase timing to beat the price rise, it can result in retailers holding stock bought pre-tariff that sits in warehouses with fewer buyers.

Even if containers are emptied, shipping companies don’t return empty containers immediately if there’s no corresponding export cargo, as moving empties costs money without freight revenue. Terminal yards and inland depots fill with empty containers waiting to be repositioned.

Ultimately, reduced demand leads to fewer ships operating those routes. Carriers avoid sailing half-empty vessels, so with falling volumes, they cut capacity through “blank sailings” (route cancellations). This reduces overall system capacity, driving up freight rates globally to balance the books.

Everyone pays.

The Cost of the Repositioning Containers

The industry works on a balance of trade. A full container arriving in the U.S. is unloaded and then needs to be filled, or at least repositioned, to return to Asia.

If fewer goods are going between China and the US, those containers will stack up in US ports due to the huge trade deficit. It imports far more goods, including furniture, than it exports.

This imbalance is not new and is a key backdrop to why tariffs are being implemented.

Before the trade war, the import-export balance in the U.S. trade with China was around 2:1. That means for every two Chinese containers that were imported, only one U.S. container was exported to China. In 2018, the total number of empty containers handled by the 10 largest container ports in the United States increased by 5.6 per cent to a record of 10.89 million TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units), with the handling of these empty containers soaring to 25.6 per cent. That increased the ratio to approximately 3:1. (Trade War, Containers Don’t Lie, Lori Ann LaRocco, p.129).

According to DAT Freight & Analytics (2023), roughly three out of every four containers arriving at the U.S.’s three largest ports: Los Angeles, Long Beach, and New York/New Jersey, are sent back empty. These ports handle nearly half of all loaded import containers in the U.S., making the 75% figure especially impactful.

To solve the empty container problem, the U.S. would need to substantially increase exports to Asia, a theoretically straightforward but practically complex challenge in reality.

Until then, carriers will continue to reposition empty containers using sweeper vessels at great expense. That cost is distributed globally, raising freight rates for everyone—including UK furniture importers and retailers.

The Cost of Sweeper Vessels and Container Imbalances

“Sweeper vessels are dedicated vessels sent by international carriers for specific purposes. They can load and move out empty containers at the ports to a specific destination at the expense of shipping lines.” — MAERSK, What are sweeper vessels?

When tariffs disrupt trade flows, carriers deploy sweeper vessels, ships dedicated to repositioning empty containers back to exporting countries.

While this helps rebalance container availability, it carries hidden costs.

- The Cost to Shipping Carriers: A sweeper voyage generates little to no freight revenue. Carriers cover fuel, crew, and port charges without income and must recoup these losses elsewhere.

- The Cost to Importers and Exporters: To offset losses, carriers increase freight rates on other routes, such as China–UK furniture imports.

In practice, the cost of solving the imbalance gets passed through the system.

While some may argue that U.S. tariffs will push down Chinese factory prices and shipping costs, the reality is somewhat different. UK retailers are unlikely to benefit from the tariffs and will probably face higher landed costs as freight lines recoup losses globally.

What we’re seeing in the relationship between tariffs, container shortages, and supply and demand isn’t the bullwhip effect in the textbook sense—but it behaves similarly. A relatively small policy change in the U.S. (tariffs on furniture) flicks the whip: import demand slows, containers pile up at ports, and carriers respond by cancelling sailings or deploying sweeper vessels to rebalance. The crack of the whip is then felt far beyond the U.S. market.

The Counterargument: Shipping Prices May Decrease

Could shipping prices come down as a result of the U.S. tariff on furniture imports? Yes, it is possible. However, it is far less likely.

For prices to drop, the supply and demand equilibrium would need to be perfectly balanced. If demand for U.S. imports declines, more containers may accumulate in Asia. But if demand drops significantly, carriers may implement blank sailings—cancelling some voyages.

This typically leads to fewer ships operating and likely a slight increase in shipping prices.

If shipping prices did decrease to stimulate demand, the reduction would probably be minimal, as a significant price drop would cause demand to rise rapidly, pushing prices back up and reducing demand again.

Therefore, while tariffs may cause some price decrease, it would only happen under optimal market conditions.

The Political Lock-in Effect of Tariffs

If tariffs are implemented and succeed in creating even a small number of U.S. manufacturing jobs, it becomes politically difficult for any subsequent administration to reverse them. A president can campaign on the simple, powerful message of “bringing jobs back.” If a factory opens in North Carolina because of these tariffs, that becomes a tangible political win.

If a future president removes the tariffs and that factory closes a year later, it creates a major political liability. It’s a difficult story to spin, and it can be used against them in re-election. This dynamic makes it highly likely that any tariffs successfully driving domestic production will become a semi-permanent feature of trade policy. They may be tweaked or reduced over time, but a full reversal becomes a political risk no leader wants to take.

History supports this pattern. For example, the U.S. tariff on imported light trucks imposed during the 1960s—known as the Chicken Tax—remains in place more than fifty years later, long after the original trade dispute faded. Similarly, despite changes in administrations, tariffs on solar panels and washing machines introduced during the Trump presidency have largely been maintained under the Biden era, reflecting the political difficulty of removing tariffs once they are perceived to protect domestic jobs. This shows how tariffs tend to outlast the circumstances that “justified” them, especially when domestic jobs are at stake.

What UK Furniture Retailers Need to Know

Don’t Expect Lower Prices

Even if some factories in China have extra stock, cheaper furniture isn’t guaranteed. Disruptions on major trade lanes like U.S.–China routes ripple globally. Higher shipping costs, container shortages, and global supply chain disruption can offset any factory discount. In fact, the overall trend is likely toward more volatility and potentially higher costs, not bargains.

Diversify Your Suppliers

Relying on a single country or trade lane is risky. Look at sourcing furniture from other parts of Asia, like Vietnam or Malaysia, and even Europe. This “China+1” approach spreads the risk. However, the proposed tariff on furniture appears to be global, so it may impact you regardless of the country of export. Furthermore, as more businesses diversify, competition for production in these countries can also push prices up or lengthen lead times.

Revisit Your Stock Strategy

Given shipping delays and potential price swings, it may be wise to hold slightly more stock of your best-selling products. This acts as a buffer against delays or sudden cost increases and helps keep your shelves stocked when your competitors might struggle. However, the trade-off is reduced cash flow tied up in stock, which may not be a viable option for many importers or retailers currently.

Keep Your Freight Forwarder Close

Your freight partner is your eyes and ears on the ground. Ask them how these tariff changes might affect Asia–Europe shipping, verify schedules, and get their insight on pricing trends. They can help you anticipate delays and identify cost-saving opportunities.

What Will Be the Impact of the US Furniture Tariffs

The reasoning behind the tariffs, not the Make America Great Again, but to improve conditions for the American people, is understandable, and echoes similar sentiments in other countries. However, the distorted perspective that seems to be at play, which is that it’s better to be feared than loved, often attributed to Machiavellianism, is not something I agree with.

So far, the tariffs have acted like a thumbscrew tactic affecting the global status quo. Typically, the winners in such a situation are those who are proactive. Yet, the flip-flops and delays in tariff implementation have arguably caused as many, if not more, problems than the tariffs themselves. This uncertainty mirrors what was seen with Brexit and its deadline extensions.

The idea that U.S. tariffs will lead to cost reductions for UK furniture retailers is a dangerous oversimplification. The reality is these tariffs disrupt a complex, interconnected global supply chain, disrupting the flow of containers and creating unpredictable pricing. This is unlikely to be a temporary blip—instead, it represents a fundamental change that will cause volatility in the market for some time.

From my perspective, instead of imposing tariffs across the board, the government should consider exempting intermediate goods used in U.S. furniture production—such as screws, wood, and other components—from tariffs. This would allow those who can afford American-made furniture to support it without penalising those who rely on imported goods. The U.S. manufacturing sector, at current levels, cannot meet all domestic demand and will continue to need imports.

If tariffs stimulate growth in the U.S. furniture sector, there is a risk of oversupply for the market size, leading to squeezed margins. This has occurred before under the 232 proclamations with steel and aluminium tariffs, where increased production capacity suppressed prices.

Unless tariffs are set at a sufficiently high level, American-made goods will remain more expensive than imported finished products. However, too high a tariff could provoke stronger retaliatory actions from exporting countries.

All of this is speculative—the true scale and global impact of furniture tariffs are yet to be seen. Will any tariffs be imposed at all? It remains a waiting game.

Until then, the true value proposition for UK retailers lies in the quality of their furniture, the excellence of their service, and the trust in their brand. It’s not about winning a price war—it’s about building a business that can withstand post on Truth Social.

U.S. Furniture Tariff Updates

- August 30th, 2025: A federal appeals court ruled that President Trump’s broad tariffs on imported goods, including furniture, exceed his authority under emergency powers and are largely illegal, delivering a major setback to the administration’s trade policies. The ruling is under appeal, leaving uncertainty over the future of these tariffs. (Source: CBS News)

- October 14th, 2025: They are here “a 10% tariff on softwood lumber and timber imports will apply as of Tuesday. A 25% tariff will also apply to imported kitchen cabinets and vanities – rising to 50% on 1 January – and a 25% tariff on upholstered wooden furniture will increase to 30%, unless new trade agreements are reached.” (Source: BBC News)

As mentioned in the main article’s conclusion. Tariffs on intermediate goods, the soft lumber and timber quoted, could have been reduced or made tariff exempt. The lower cost would allow for increased margins to which the companies would need to invest in US saw mills and move away from imported lumber over time, which could be a condition of the tariff exception in the first place. However it could just accelerate the closing of US sawmills. A better approach may have been to subsidise the use of US mills and the same time as increasing tariffs. The current policy risks being inflationary for the furniture industry (by increasing lumber costs) without being sufficiently stimulative for domestic sawmills (which may lack the immediate incentive/capital to ramp up production). It suggests the government might be protecting the upstream suppliers (the sawmills) at the expense of downstream stability (the furniture industry). Presuming they haven’t already, to confirm if subsidies are a better fix than tariffs, they need to quickly find out exactly what investment US sawmills need to become fully competitive.

-

November 10th, 2025: IKEA profits plunge more than a quarter after Trump’s tariff uncertainty (Source: The Independent)

- December 5th, 2025: “IKEA plans to source more products from factories in the United States, the Swedish furniture group’s top supply chain executive told Reuters, as President Donald Trump’s tariffs drive up the cost of importing bookcases, mattresses and sofas.” (Source: Reuters, IKEA to ramp up US production as tariffs bite)