Escaping Price Wars: Why Your Brand is the Only Barrier

Jack Young

- Last Updated: 11 December 2025

The Gist - Why Your Brand is the Only Barrier to Escaping Price Wars

The UK furniture market is squeezed from both ends: low-barrier online entrants commoditise product from the bottom, while oligopolistic giants use scale to set the tone on price and promotion from the top. Porter’s Five Forces illustrate that this structure naturally drives margin erosion, amplified by CMA limits on resale price maintenance and supplier imitation that speeds up diffusion and dulls differentiation.

For independent retailers, competing on price, scale, or product alone is unwinnable. The only durable defence is a brand. Built as a risk-reducing economic moat through intangible advantages like trust, expertise, and a superior customer experience that create high emotional switching costs.

For independents, this means you must

- Define a clear, specific brand promise that speaks to a segment (service-led, design-led, sustainable) rather than “good furniture at good prices”.

- Curate your range and suppliers to support that promise, avoiding me-too lines that have visibly entered commodity territory.

- Design your sales, delivery, and after-sales experience to make buying from you feel safer and more supported than cheaper alternatives.

- Invest in relationship-building content and communication so loyal customers feel too much risk in switching to unproven newcomers.

Table of Contents

A Furniture Market Under Siege

It can feel like an almost daily occurrence, a customer says that they were looking at or, worse, bought from another shop or website that you have never heard of before.

Great! Another competitor to protect margins against. Another player accelerating the race to the bottom on price.

The low barriers to entry in the furniture retail industry are a major reason why so many new businesses keep appearing, intensifying unhealthy rivalry. Easy access to global supply chains and low overheads for e-commerce mean anyone can start selling a sideboard or dining set relatively quickly and for lower margins than current retailers. And because most products look similar across retailers, low product differentiation only fuels that rivalry further.

But what can you do? Is there even anything you can do to protect your business against this relentless pressure?

Yes, there is.

And while you may be bored of hearing me say you need to build a brand… You need a brand. You need to stand for something. You need to differentiate in a way that actually benefits and attracts the consumer. Creating a high barrier for competitors to cross.

There’s strong evidence that when a retailer builds a brand that genuinely stands for something, clear values, consistent quality, and trust, customers are far more likely to stay with them. A recent study in the retail sector found that customer-perceived value, service quality and, importantly, brand trust all have a direct, positive effect on customer retention.

A strong brand is the only sustainable defence against the low barriers to entry that are tormenting the UK and global furniture market.

The Market Structure: Monopolistic Competition with Oligopolistic Elements

To truly understand the pricing pressures and margin erosion plaguing the B2C furniture sector, we must first examine the deep-rooted market structure that naturally leads to intense competition.

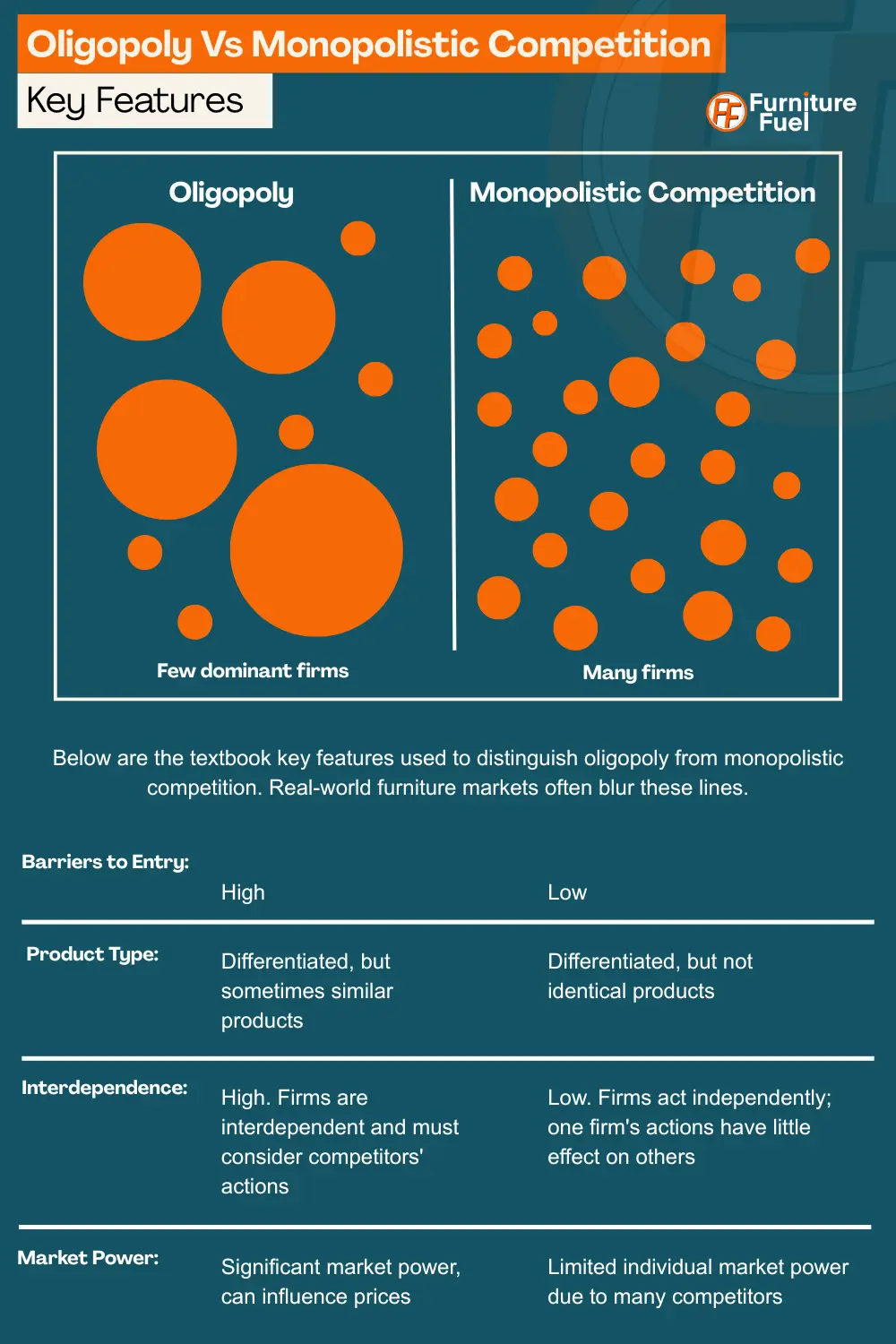

The UK furniture retail environment can be thought of as one of Monopolistic Competition with Oligopolistic tendencies.

I know—I normally avoid these terms because they give people headaches. But stick with me.

On one side, you have the Oligopolistic Leaders, a handful of dominant national chains (e.g., IKEA, DFS, Dunelm J Sainsbury plc) that command a large percentage of the market, particularly in categories like upholstery. Their scale, purchasing power, and advertising budgets create a severe barrier to entry for similar-sized brands.

On the other side, you have the vast, fragmented buyer base, where the thousands of smaller, independent retailers operate under Monopolistic Competition conditions. It is the growth of e-commerce, DTC logistics, and drop shipping that has lowered effective barriers to entry, making it easier for new niche brands to enter and adding to fragmentation.

Oligopoly (The Dominant Giants)

An oligopoly is characterised by a few dominant firms that collectively control a substantial portion of total market revenue. For any potential newcomer, the High Barriers to Entry at this level are immense, requiring substantial capital investment for large-scale showrooms, national logistics, and major advertising campaigns. A key characteristic is Interdependence. The strategic actions of one giant directly impact all the others. If a dominant player launches a major, sustained promotional event, the rival large chains must immediately respond, setting the tone for pricing and discounting across the wider market.

Monopolistic Competition (The Fragmented Market)

Monopolistic competition is characterised by a lot of smaller firms competing with products that are differentiated by brand, service, style, or perceived quality, not by price alone. Each retailer has a slight ‘monopoly’ over their unique offering and customer base, allowing some limited control over their pricing strategy. However, this competitive space is highly vulnerable due to low barriers to entry, meaning new niche and online businesses constantly flood the market and erode the exclusivity of product offerings.

The Monopolistic Competition Component (The 'Fractured' Side)

In the UK furniture market, there is a large number of businesses operating that are not large multiples. Most of the retail sector is composed of thousands of independent and specialist retailers, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs).

Product Differentiation

The monopolistic component of this market structure is that products are rarely identical or should not be. Retailers must compete by offering differentiated products based on:

- Brand/Design: Offering exclusive products or distinct, curated design selections. For example, a customer choosing a bespoke sideboard over IKEA, or favouring a brand that aligns with their sustainability views.

- Quality/Material: Specialising in superior construction or sustainable sourcing. For example, a retailer focusing on handmade, FSC-certified oak furniture

- Location/Service: Building loyalty through high-touch physical service. For example, a local independent shop offering personalised consultations, white-glove delivery, and robust after-sales support such as assembly, repairs, and flexible returns.

- Customer Experience: Investing in a seamless, premium journey. Utilising technology (AR, 3D visuals, polished websites) to enhance the journey rather than just push products, and offering flexible payment and delivery options.

Product Similarity, Me-too Strategies, and the Real Nature of Differentiation

It has been my experience, however, that a textbook definition of differentiation rarely reflects what happens among smaller independent retailers in the furniture market. In practice, many gravitate toward a me-too approach, replicating competitors’ product ranges, pricing, support services and infrastructure.

A lack of meaningful differentiation often signals a lazy market, a market running on habit rather than intention. Because customers will always need furniture, some retailers put little effort into enhancing the product or elevating the buying experience. This isn’t just uninspiring. It creates unhealthy competitive forces. These businesses unintentionally drag the market into a race to the bottom.

To be clear, analysing the competition to see how you might improve offerings for your audience is wise. Copying products, ideas, or service models without thinking about how it strengthens your brand or deepens your relationship with customers is not.

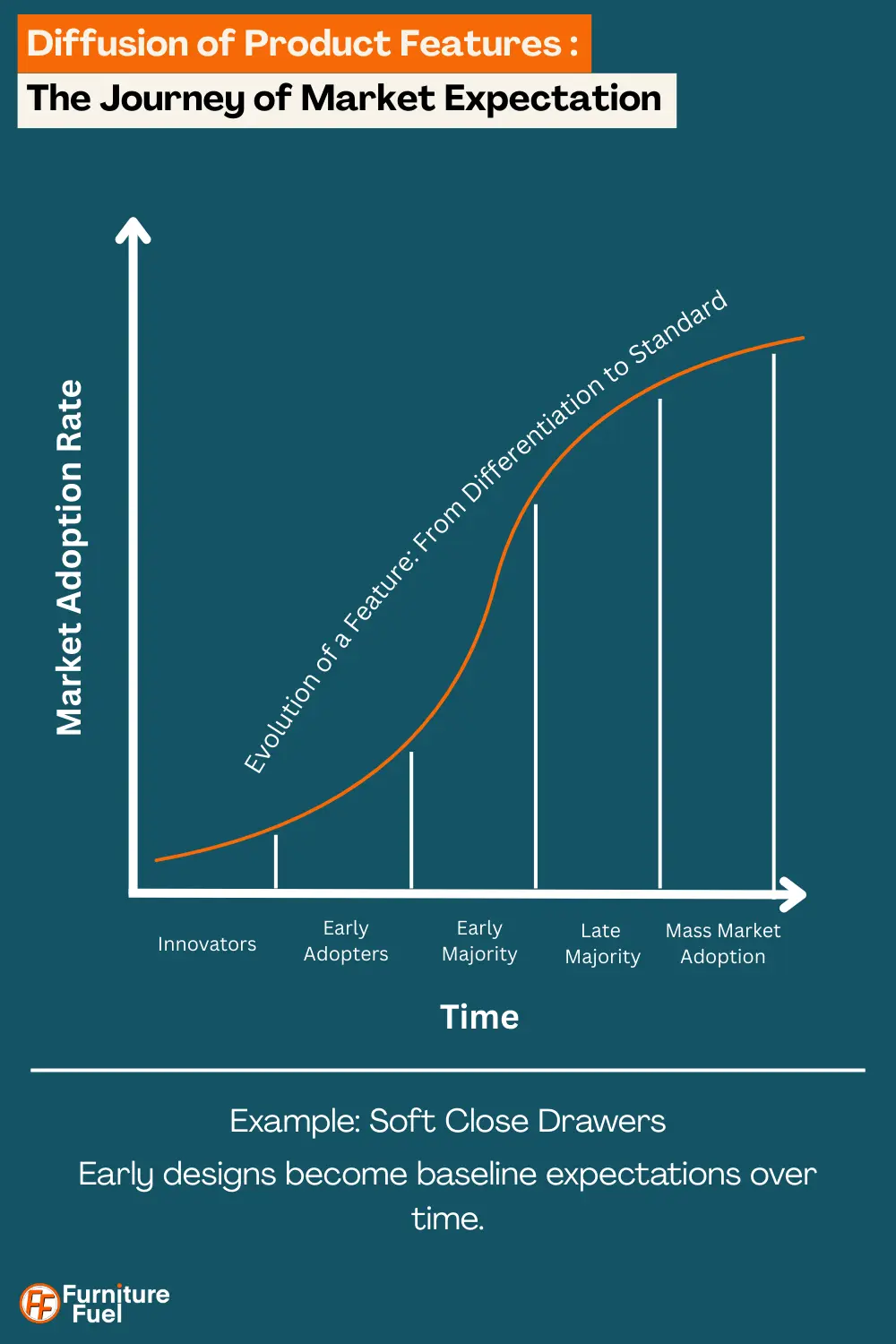

Of course, there are also instances where copying is not lazy imitation but simply meeting market expectations. When enough competitors adopt a feature and customers come to see it as standard, not offering it means you’re no longer meeting even the minimum acceptable level. This becomes a case of product diffusion.

The Diffusion of Innovation Theory, developed by sociologist E.M. Rogers in 1962, argues that ideas and innovations spread through a population until they’re eventually adopted by the mainstream. Furniture follows the same pattern. Features that begin in premium ranges eventually spill over into mass-market, a natural evolution of the category and its products.

Many features we now think of as standard first appeared on the Mercedes S-Class. Anti-lock brakes (ABS) and airbags are the most widely recognised. Eventually filtering down to every new car segment. Similarly, features like soft-close drawers started as premium distinctions and are now diffusing to become standard market expectations.

Over time, this diffusion erodes genuine differentiation, making proactive brand development even more important.

This principle applies across all channels. Digital-first retailers are increasingly investing in virtual showrooms, leveraging user-generated content, and collaborating with influencers to create immersive online experiences. Tools like AR and 3D visualisation are no longer gimmicks. They’ve become essential for maintaining a competitive customer experience, but they are no longer a source of unique brand advantage.

There are no barriers to joining our newsletter—just insight on how to build your own

The Oligopolistic Component: The Dominance of Giants

This side of the market sees a concentration of power among a small number of major national chains, such as IKEA, DFS, Dunelm, John Lewis, and SCS. Collectively, these retailers command a substantial portion of the overall market revenue.

This dominance is even more pronounced in sub-sectors. For example, DFS Furniture plc (including Sofology and The Sofa Delivery Co) holds a significant share of the upholstered furniture market. At approximately 39% (based on GlobalData figures cited in DFS’s own annual report), this market share statistically places them within the criteria for a Working Monopoly position in that segment.

A ‘working monopoly,’ as defined by the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), is any firm holding more than 25% market share. Importantly, this threshold signals significant market power, but it is a classification criterion and does not, by itself, confirm anti-competitive behaviour.

However, in complete fairness to DFS, what was interesting reading their annual reports and accounts 2025 was the focus on NPS Scores or Net Promoter Scores, of which their post-purchase NPS was reported at 91.8%. A strong focus on customer satisfaction may account for their dominant upholstery market share, as opposed to purely relying on scale.

The actions of these giants, like running continuous major sales events or price promotions, significantly impact the strategies of their direct competitors and the smaller retailers below them. This interdependence is the core, defining feature of an oligopoly.

These large retailers benefit from substantial economies of scale in purchasing, logistics, and national advertising, creating a high barrier for small firms to challenge them on price and volume.

The Reality of the Furniture Market Structure for SMEs

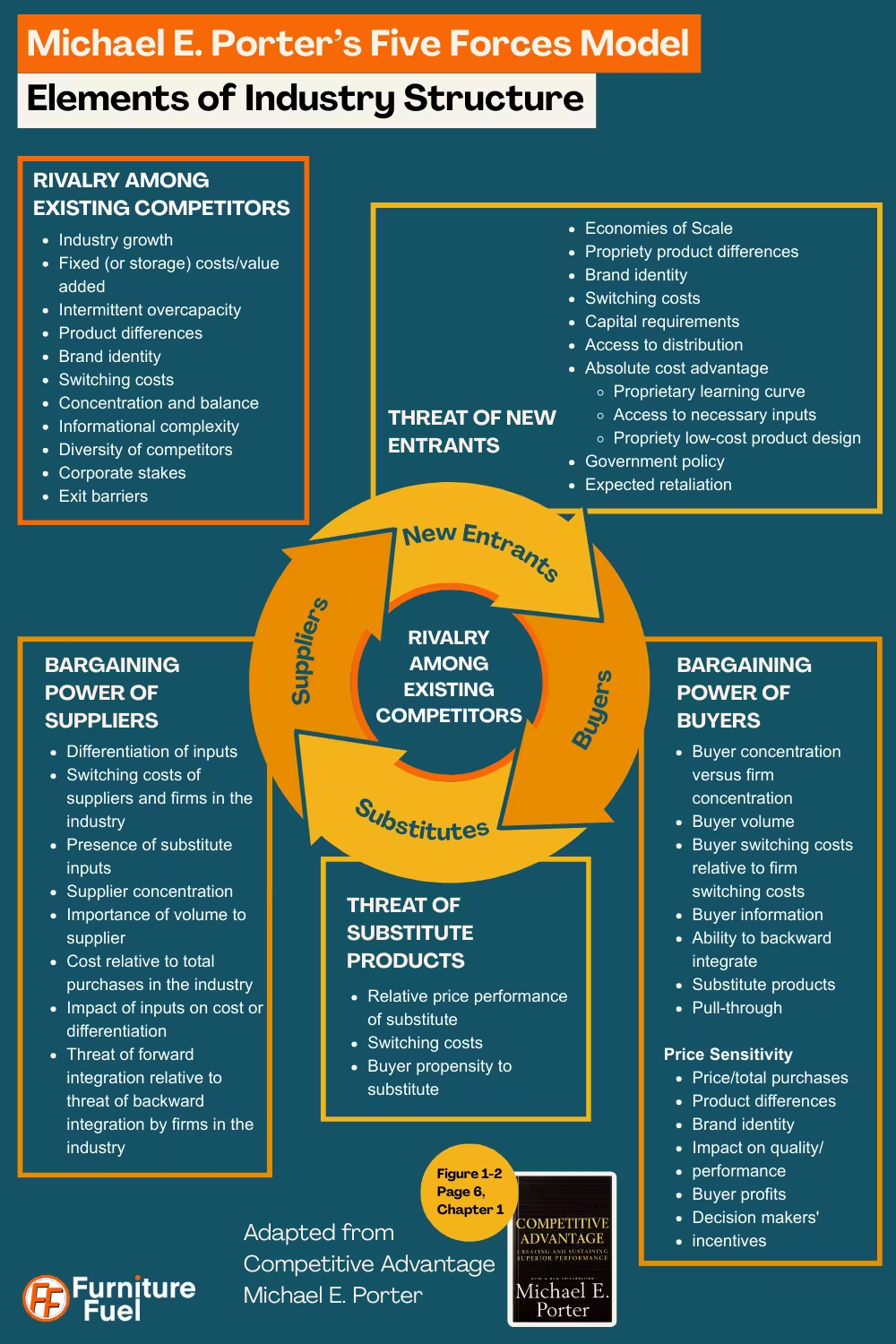

Using Michael Porter’s Five Forces model to analyse the competitive intensity of the market, we can get a realistic, albeit static, view of the current market’s intensity.

Michael Porter’s Five Forces Model

Michael Porter’s Five Forces Model is a framework for analysing the competitive intensity and market attractiveness of an industry. It helps businesses, like furniture retailers, determine where the power lies and how profits are distributed.

The core concept is that competitive rivalry is not just about existing competitors, but is shaped by five distinct pressures, or ‘forces’, that collectively determine the industry’s long-term profitability and its structural weakness.

The Five Forces are:

- Threat of New Entrants: How easily can new firms join the market? (Low barriers = high threat).

- Bargaining Power of Buyers: How much influence do customers have to push prices down? (High when buyers are few or switch easily).

- Bargaining Power of Suppliers: How much influence do suppliers have to push prices up? (High when inputs are essential and substitutes are few).

- Threat of Substitute Products or Services: How likely is it that customers will switch to an alternative, even from a different industry? (A new kitchen or holiday, for example, can be a substitute for a new sofa purchase).

- Rivalry Among Existing Competitors: How intense is the competition between current players? (Price wars, high advertising = high rivalry).

By assessing these forces, you can identify the structural barriers that need to be built to protect margins and secure a defensible position in the market.

A Quick Word on AI

AI isn’t mentioned below. The reason for this is that while AI is emerging as a disruptive force across all sectors and will without question change many markets, the long-term forecasts of its effects remain speculative. Those speculations suggest AI could, over time, moderate the threat of new entrants by only suggesting strong brands that align with customers’ wants and needs, using established brand data and amplifying the customer relationships. Making a less proactive individual less likely to enter. At present, though, entry barriers are still relatively low for many online retailers using a D2C or dropship model.

Porter's Five Forces: The Current Furniture Market

Threat of New Entrants: High

This is a core challenge for the industry right now.

While opening a physical shop can be costly, with all that is required to operate it, with drop shipping models and B2C platforms, a new competitor can launch a website and start selling furniture with minimal capital investment and no need for a physical showroom, warehouse stock, or delivery fleet. The constant influx means the market becomes continuously diluted.

The negative impacts on price and margin aside, it could be argued that low barriers to entry mean better offerings for buyers, a more competitive market. This is true in theory, but the majority of the time, “better” comes in the form of low-quality, low-cost products, with a low price tag. A wolf in sheep’s clothing.

There is a cost to the customer when everyone is focused on the lowest price. Something has to give. It might be in the form of poor-quality materials, weak after-sales service, or a lack of proper warranty support. The “hidden cost” of this commoditisation is a poorer overall experience for the end user.

Good on the face of it for the customer short term. Long term, though, these low-cost entrants could cause you to go out of business, leaving the customer with only these low-cost offerings.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low to Medium

For the vast majority of suppliers who produce commoditised goods (like a standard sofa or bed frame), their power is low. There are thousands of manufacturers, especially in the Far East, selling very similar products. However, for a select few unique, high-demand, or designer brands, their power is medium to high. These brands can command higher prices and dictate terms to retailers, and retailers will accept it because the product itself is a draw.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

The buyer has never had more power. Customers can compare prices and products instantly online, read reviews, and find alternatives from around the world. This abundance of choice and information means that the customer can often influence or even dictate the price, not the retailer. This pressure is a direct cause of the margin erosion.

The vast amounts of comparable product information have created, in a way, an ironic situation, the Retailer’s Lemon Problem. The customer now possesses superior pricing and product knowledge. The independent retailer cannot possibly track every competitor’s offering, leading to internal uncertainty. They don’t know if their own product is the ‘lemon’ versus an ever-changing sea of competitors.

Escaping this squeeze requires a strategic pivot away from price competition entirely.

We must also acknowledge the rise of marketplace giants such as Amazon and Wayfair. They have not only further lowered barriers to entry, allowing new suppliers to reach vast audiences instantly, but they also excel at showing alternatives and substitutes to the initial product searched.

The Lemon Problem

This concept refers to the problem of asymmetric information, specifically, the customer’s difficulty judging the quality of a product (like a mattress or sofa) before purchase. When product quality is uncertain or hard to determine, the market tends to gravitate to the lowest-priced offering, punishing higher-quality retailers who cannot easily prove their superiority. Find out more about the lemon problem in our article on how mattress machines built trust.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium to High

Any purchase that achieves the same aesthetic or functional goal is a threat. The purchase of new furniture has been, in my experience, rarely due to the end of life of the current furniture, but more to do with a change or refresh. It can also be due to the following trends, like the everything must be grey era.

So, depending on the goal, a customer looking to refresh their home might consider new flooring, windows or a kitchen upgrade as a substitute for new furniture.

This may still result in new furniture being purchased, as the old furniture may now stick out to them with all the new surrounding elements. A delay, though, can mean more time to consider alternatives, which is never a good place to be for a commoditised product offering.

Then there is the decision not to buy anything at all because their existing furniture is “good enough”, which is still a substitution. This is the primary competitor to all furniture retailers, especially when buying becomes confusing, and friction to the purchase is added.

Rivalry Among Existing Competitors: High

This is the inevitable outcome of the other four forces. With so many sellers in the market, and products that are often difficult to differentiate, all competing for a powerful buyer with multiple substitution options, the rivalry is intense.

It would not be a fair market assessment, although normally done via a PESTEL analysis, without discussing current macroeconomic forces, including high inflation, interest rate fluctuations, freezing tax thresholds and the cost-of-living crisis.

These macro factors have dramatically reduced discretionary spending, not just on furniture, but on all non-essentials. These pressures reshape consumer confidence and amplify pricing competition nationwide. They do potentially raise barriers to entry. If spending is down, new entrants may not be keen to enter the market, but this brings little comfort to anyone.

The overall result of intense rivalry often leads to a constant state of price wars to grab a share of a very fragmented market, which is especially true in a large market.

Taken together, Porter’s Five Forces expose an industry currently structured for intense competition and persistent margin erosion.

But before discussing what you can do, the question must be asked: could suppliers do more?

The Suppliers' Distribution Dilemma

From the supplier’s perspective, more stockists mean a wider audience reached and theoretically more sales volume. Additionally, more stockists, especially in a geographical area, can spread the costs of a delivery. Five shops in relatively close proximity to each other are more cost-effective than two shops spread miles apart.

However, the ‘maximum distribution’ approach has long-term damage. The consequence is that when every town has shops selling the same sofa model, for example, the sofa and the associated brand begin to lose their appeal. They become common and lead to easier price comparison, eroding the retailer’s ability to invest in quality service, showroom space, and marketing, which help to sell more of the supplier’s products in the long run.

A Return to Strategic Partnerships and Exclusivity

This idea is nothing new. Exclusivity has been around for a long time, but its prominence used to be more of a thing. Perhaps it still is, but it’s not discussed as much as it once was.

There is a case for its return or resurgence, even if it’s on a micro-geographic level.

Exclusivity incentivises retailers to invest in that product, knowing they won’t be undercut locally. They may give it a prime location, spend more on marketing it to their audience than they would on other mass market products. It builds a genuine partnership, not just a transactional relationship.

This could be offered on a 6 or 12-month commitment. In return, the retailer must meet specific performance metrics (sales, showroom display, staff training). If the metrics aren’t met after the agreed period, then the supplier can reassess and potentially open another account in the area. This is a mutually beneficial, data-driven decision, not a knee-jerk reaction.

The goal for both suppliers and retailers should be to increase the orders and protect margins, not simply to chase volume. A market with fewer, but stronger, independent retailers is far more resilient and profitable for everyone involved.

This route of exclusivity also protects the supplier’s brand. When suppliers control more of the downstream channels (the stores, the websites, etc.) in which the products are sold, then they help control the overall brand positioning and customer experience.

The Imitation Over Innovation Design Problem

There does seem to be a sense that, among a significant number of suppliers, there has been a shift away from a design-first mentality. Instead of investing in creating truly unique, trend-setting pieces, they’ve adopted a reactive, copycat approach. A lack of genuine innovation from suppliers is a major pillar of the problem, which feeds directly into the issues of market commoditisation and the need for retailers to build their own brand.

Now, yes, these are sweeping statements and generalisations. There are some fantastic suppliers in the industry with thoughtfully designed furniture. However, even those suppliers will admit that imitation is a problem and is more common now.

When times are tough and profits are squeezed, it’s easier to copy than to spend money on research and development, risking money on furniture that might not sell.

A supplier may see a successful sofa, sideboard, or bed from a market leader and instruct their factory to produce a similar version. They might alter the stitching, change the leg style, or offer a different fabric, but the core design is a direct imitation.

For retailers, this creates a major headache. If a supplier’s catalogue is just a collection of imitations, what makes their offering special? The market becomes a sea of similar products competing on price, and a supplier’s original, unique designs get lost or are not developed in the first place because the perceived risk is too high.

A retailer can’t build a reputation for selling unique, high-quality furniture if their supplier’s range is uninspired and easily found elsewhere. They become just another stockist of generic items, not a destination for something unique.

It reinforces to the customer that everything is the same, making them more likely to just look for the cheapest option online.

The Role of Strategic Product Curation

Product Curation is the act of thoughtfully selecting and presenting a collection of products, much like an art exhibition, that precisely addresses the needs and tastes of your specific audience. Your shop or website is essentially a place that the audience knows they can go to find what they need, confidently bypassing the ‘sea of sameness’.

You must be mindful of what customers are saying, especially when they’ve seen a product cheaper elsewhere. This feedback is a vital source of intelligence. If a customer says they’ve found the “Meredith” sofa or something similar cheaper, that’s not just a potential lost sale. It’s a signal.

This feedback indicates that the product has potentially entered commodity territory. Its value is no longer in its design or perceived exclusivity, but purely in its price. When this happens, a retailer has two choices:

- Join the price war: Compete on price, which erodes margins and devalues the brand. This is a losing strategy in the long run.

- Change the offering: Use the feedback as a prompt to evaluate the product. If a line is being widely copied or sold at a lower price point elsewhere, it’s time to find a new offering that fits your brand’s unique proposition.

Being Number One in The Race to the Bottom

All that was said about the supply side is great, but online and imitation are not going away.

You cannot, as a supplier, legally enforce a minimum price on retailers in the UK due to competition law. Setting prices is a form of resale price maintenance (RPM), which is generally prohibited by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). While suppliers can suggest a Recommended Retail Price (RRP), they cannot pressure retailers to stick to it or threaten to withhold supply if they don’t. Whilst selective distribution agreements can be lawful alternatives, these must be structured carefully and legally and are not used to coordinate prices or exclude competition in a way that breaches competition rules. And would most likely only be offered to strong, established brands.

The national reach of online retailers means that geographical exclusivity, while beneficial, is more like a small band-aid on a large wound. An online business in Cornwall can easily compete on price with a physical shop in Glasgow.

There is also the issue of retailers directly importing copies of popular designs themselves, bypassing suppliers entirely.

Since suppliers are either unwilling or, to be realistic and fair to them, unable to control the intensity of the market. The ultimate responsibility for survival and success falls squarely on the retailer.

They must become more than just a stockist. They must become a brand.

The Only True Solution is Building Your Brand as a Barrier

While some retailers are busy diluting the market, savvy retailers must focus on what they can control: their own brand.

Two me-too businesses selling what is essentially the same product will inevitably end up in a price war. But the retailer who has built a brand around trust, expertise, and a unique customer experience can escape this trap.

A brand is a risk reducer for consumers. It’s a symbol that signals when you buy this, it is “backed by” this brand and all they stand for. The customer is buying a piece of furniture wrapped in reputation, expertise, and after-care that comes with the retailer’s name.

Not only does the consumer get to align themselves with a retailer’s brand, which makes brand loyalty stronger as it becomes more attitudinal instead of simple behavioural, but also becomes a risk reducer for you, as a barrier to entry. When someone is deciding whether to enter a market and is hopefully doing their due diligence, when they come across an established, healthy, strong brand, it becomes a major hurdle.

At a minimum, they must match your offering to even have a hope of attracting customers. However, this alone is not enough to take your loyal customers away from you.

Yes, there are, as we call them, nomadic customers. These customers do not have a permanent home in your store. They go where the price is lowest, not where the value is highest. Don’t lose sleep about these individuals leaving. They are less likely to recommend you, less tolerant of mistakes, and more likely to take up time and resources compared to loyal customers.

Loyal customers will not leave when a comparable offering is presented. There is no need to. When you have made and kept the brand promises to the customer and have built a relationship with them and many happy buying experiences, the emotional switching cost becomes too great. They become risk-averse, thinking: “What happens if this new brand doesn’t keep its promise? Doesn’t make me feel the same way my current one does?”

This is nothing new to the large national furniture retailers. On page 50 of the DFS Annual Report and Accounts 2025, which we mentioned earlier, under SHIFT IN CUSTOMER/CONSUMER VALUE, Risk/opportunity, it states:

“Customers have demonstrated they will align themselves with brands that reflect their values. Failure to meet these shifting values could cause customers to switch to alternative products or competitors. Growing awareness of climate issues and change in consumer priorities could provide an opportunity to widen our customer base, and increase revenues, profits and market share.”

DFS recognises that it must stand for something that aligns with its audience, beyond the simple, transactional selling of a sofa. The risk level assigned to this section was low, indicating confidence that no current or new entrants can easily disrupt their ability to meet these shifting customer needs.

This mirrors Fred Reichheld’s observation, as he explains in The Ultimate Question 2.0 (p. 50),

“We also realized that two conditions must be satisfied before customers make a personal referral. They must believe that the company offers superior value in terms that an economist would understand: price, features, quality, functionality, ease of use, and other such factors. But they also must feel good about their relationship with the company. They must believe the company knows and understands them, values them, listens to them, and shares their principles. On the first dimension, a company is engaging the customer’s head. On the second, it is engaging the heart. Only when both sides of the equation are fulfilled will a customer enthusiastically recommend a company to a friend. The customer must believe that the friend will get good value-but he or she also must believe that the company will treat the friend right. That’s why the “would recommend” question provides such an effective measure of relationship quality. It tests for both the rational and the emotional dimensions.”

This distinction between “head” (economic value) and “heart” (relationship and shared values) is central to understanding why loyal customers both stay and recommend, and why emotional switching costs can be so high in categories like furniture.

The Halo Effect of the Retailer

The “halo effect” describes a situation where the good traits or reputation of one entity benefit another by association. In this instance, a positive impression of the retailer’s brand “rubs off” on the products they sell.

A customer is happy to pay a little more for the same mattress from a local, family-run shop than from a faceless online business because they trust the former’s advice and know they’ll get better support if anything goes wrong.

This shifts the consumer’s focus from “What is the cheapest price for this sofa?” to “Which retailer do I trust to provide the best advice and service for my home?”

Overall, when building a brand, you are adding to the moat around your business.

A strong brand, one that has made and reinforced its promises, adds to a business’s economic moat, a term popularised by the legendary investor Warren Buffett.

Investopedia define it as,

“…more than just a fleeting competitive edge—it’s a sustainable advantage that allows a company to outperform its rivals over an extended period. These can take many forms, but they all serve the same purpose: protecting a company’s market share and profitability from competitive forces.”

The new entrants can’t just copy. They must find those issues that your customers are complaining about and that, if solved, would be enough to get those customers to switch, or find a different, unaddressed customer segment. The latter would not, in theory, impact you as much as a new entrant taking current customers away. A brand builds a relationship with the customer, which managed correctly and continuously reinforced with each interaction, makes enticing them away much harder.

Happy, trusting customers are your loudest supporters and promoters. They will defend you when things go wrong and be more tolerant of mistakes.

Building this moat requires focus on three core components:

- Clear, differentiated promise that matters to a specific audience (e.g., sustainable, service-led, design-led).

- Deliberate product curation aligned with that promise.

- Consistent after-sales and communication that reinforces reduced risk and trust.

From a strategy point of view, for independents, everything ultimately loops back to brand. Make no mistake that a brand is not elements like logos and colours that some would have you believe. It is a comprehensive summation of the customer experience. It is not just seen but felt.

For a small or mid-sized retailer, the “defences” against low barriers to entry and price-led rivalry boil down to four categories:

- Structural cost advantages (scale, owned logistics, purchasing power) – which independents mostly cannot build to the level of the giants.

- Regulatory barriers – not realistically controllable by one retailer.

- Control over distribution or exclusivity – partly possible, but as discussed, constrained by law, online competition and product diffusion.

- Intangible advantages: brand, trust, relationships, capabilities, know-how, data, culture.

Most of the things an independent can actually choose to build (service model, curated range, values, content, expertise, post-sale experience) are, in effect, components of brand. They are how the customer experiences and interprets “who you are” and “what buying from you means”, and they are what create switching costs and margin protection.

The only feasible and sustainable competitive advantage for the independent furniture retailer lies in those intangible assets. Everything else is either outside your control or easily copied.